The Art and Science of Judging

To find order in chaos, to distinguish between right and wrong, good and bad, to discern truth from falsehood. How are we to do this, but through judgment?

They say it’s wrong to judge, but that always sounded awfully judgmental to me.

After all, we humans strive to understand the world around us – to find order in chaos, to distinguish between right and wrong, good and bad, to discern truth from falsehood. And how are we to do this, but through judgment?

But if this is the case, then why are we judged so negatively for judging? Why don’t we sing praises of our overly judgmental friends who wield the blade of Right and Wrong with fury? Instead, we call them cynical assholes. Or worse, cancel them.

Although the blade of judgment can carve out order from chaos, not everyone’s blade is battle-ready for this herculean task. Paradoxically, the duller our blade – the less keen our ability to judge – the more judgmental and cynical we become. And vice versa, the sharper our blade of judgment, the less judgmental we become.

It follows then, the antidote to an overly judgmental or cynical demeanor is not less judging, but more judging and better quality judging! It is imperative that we sharpen our blades of judgment not merely because it’s the best response to being told it’s wrong to judge, but because the very quality of our lives depends on it.

This is the story of how I came to judge more, judge better, and avoided becoming a cynical judgmental asshole in the process but I’ll let you be the judge of that. And how you can do the same.

It all began sometime last summer, the year: 2022.

My friend invited me to come with her and several other folks to watch a Slam Poetry event downtown. I’d never been to one before, so I didn’t really know what to expect. For the uniformed of you (as I was), Slam Poetry is a spoken word art form where the poet performs in front of an audience. The poems are generally quite personal and emotional, and the audience tends to get involved too.

The closest I’d come to seeing anything like it before was the Slam Poetry parody scene in 22 Jump Street. It’s not my goal to judge Slam Poetry as a whole here, but it ended up being not too far off from that scene. In a good way, of course.

Anyways, it turned out to not only be a full house at the event, but there was a competitive element as well – the top three poets of the night would be moving on to “regionals.” There were real stakes at play.

As the event began, the MC shared that we, the audience, would be the judge. Specifically, five volunteers from the audience would be responsible for these poets’ fates and their chances of making regionals.

With half the crowd eagerly raising their hands to volunteer to judge, I thoughtlessly raised my hand as well, thinking it could be fun. Somehow, I was selected as one of the five judges. And then I remembered – I was but a foreigner in the Slam Poetry scene, a Slam Poetry virgin if you will, and I had no idea how to judge these people. How am I supposed to decide who gets to move on to regionals? My ignorance could end a skilled wordsmith’s career. Or worse, catapult an undeserving jabroni to stardom. Thoughts of such responsibility coalesced as an anxious knot in the pit of my stomach.

To give a little context, I don’t consider myself completely clueless when it comes to judging spoken word performance. When I was a freshman in high school, we had a grade-wide competition called the “declamation.” Every freshman English class in my school was required to read the ancient Greek classic The Odyssey. At the end of the year, we could choose any 30 lines of the classic to memorize and perform in front of our peers.

There was a rigorous judging process for the performances. The rubric consisted of a variety of different criteria, such as accuracy, tonality, body language, emotionality, eye contact, etc. Even the short description describing the meaning of the chosen passage each student gave before the actual 30-line performance was taken into account. Altogether, the scores were summed to give each declamation a cohesive rating out of 24. Of course, a perfect 24 was unheard of, anything over 20 was considered excellent.

After having practiced my declamation a fair amount, I surprised myself and won the competition. However, this meant that each and every following year in high school, I was one of the judges on a panel of judges composed of other former declamation winners and English teachers to judge that year’s freshman declamation. I was now responsible for putting younger students through the same rigorous 24-point rubric that I had survived. And I took the job very seriously.

Back to summer 2022, Slam Poetry event. Just as my responsibility as a judge coupled with my Slam Poetry virginity began to weigh on me, forming that anxious knot in my stomach, I remembered who I was: former declamation champion, 3-year declamation judge. I got this.

As the MC proceeded to tell us the rules for judging, I was prepared for whatever complex rubric they had, be it 24, 36, or, hell, 48-point. After all, this wasn’t my first rodeo, and I was determined to be a fair arbiter of truth in this competition. No undeserving jabronis would be making regionals under my watch.

So, as for the rules for judging? What was the rubric – the holy rubric – to use as an objective, impartial standard of judgment amongst all competitors? None. The MC instructed that each of the five judges were to give each performance a single rating, 0 to 10, decimal points included. That was it. The anxious knot in the pit of my stomach re-coalesced.

And then the competition began.

Judgment – it plays a clear role in trials or, in this case, Slam Poetry. But it extends far beyond the courtroom or the stage. If you think about it, isn’t the vast majority of everyday communication simply judging and sharing judgments?

“What do you think about that Italian restaurant on Broadway?”

“Did you like the new Marvel movie? Is it worth watching?”

“Joey’s great, but he has an Android… So I don’t think it’s gonna work out.” (Disclaimer: I’m actually a happy Android user, but I need to relate to and appease the masses here…)

Judgment lies at the core of decision making as well. Not just the small ones, like which coffee to order, but the big ones too – is it worth moving cross country for that job? Or, is she the one?

The way we judge the world comes from the way we view the world. And how we view the world – through whatever mental models we have spent our entire lives building (or being given) – is everything. It dictates the quality of our lives, careers, relationships, and ultimately how successful we are in fulfilling that core human need of distilling order from chaos, making sense of the world.

So it’s not a question of whether it’s right or wrong to judge (a paradoxical question in and of itself), but to examine what mental models we have that create our judgments.

Yes, these were the thoughts that began to race through my mind as that first poet stepped up to the stage. Like I said, I took my job as judge seriously. Not only because of the external ramifications, but the internal ones too.

He was a shorter Asian fellow with a darker complexion and thick glasses. For the next three minutes, he entered his rhythmic flow, expressing what life was like growing up as a Filipino in California. As a fellow Filipino (well, half), he had my ear. I was trying to relate, but his life sounded pretty brutal. Something I would quickly realize was typical of Slam Poetry (at least the ones I heard that night) is the sharing of one’s suffering and grievances with the audience, and the audience responding to each injustice with sounds of validation. It’s kind of like artistic vent therapy for the poet.

The allotted three minutes were up and the MC asked that each judge give their rating. Having been given scorecards, all we needed to do was raise our ratings above our heads for the MC to read aloud. There was no anonymity.

With no rubric or scoring system given to us, I scrambled to approximate my own based on my experience judging declamations in high school. I decided to take into account as many relevant variables as possible – body language, pacing, vocal expression, etc.

The other four judges were quicker to give their ratings.

“9.2!” Exclaimed the MC, followed by a roar of cheers from the audience.

“9.1!” Followed by more cheering.

“Another 9.2!” The cheering amplified.

The judge beside me lifted his card. “Ohh, an 8.2.” the MC said flatly. The once energized crowd hit a wall – only some sparse clapping and even a couple “boo’s!”

Internally gasping to myself, I couldn’t believe an 8.2 wasn’t deserving of a more enthusiastic response from the audience. And I was about to give a 7.5! If that’s how they responded to an 8.2, I would lose all reputability as a judge with my harsher rating.

I scrambled to change my scorecard at the last minute. I didn’t want to start an angry mob so early on.

“C’mon judge number five! I need that rating!” The MC called out.

Finally, I found what I was looking for and raised an 8.6 above my head.

“Our final score, 8.6!” Followed by a few more claps and even a few “whoo’s!”.

Relieved, I mentally prepared myself for the next contestant.

The night was a flurry of all different types of poets, ranging from late teens still in school to at least one who likely lived in a nursing home. Men and women, every hair color imaginable, from blue to red, green to yellow.

It was a constant balancing act as a judge – I remained faithful to what I believed was a fair rubric while attempting to remain relatable to the crowd and not diverging too far from the other judges’ scores. After all, I considered myself a visitor in this strange new world of Slam Poetry, and didn’t want to rock the boat too much. Throughout the night, I experienced my fair share of groans and a few “boo’s,” but also some validation and cheering to balance it out.

The event was divided into several rounds, where poets would be eliminated in each round, until the final round where only three would move on to regionals.

As we began the second to last round, I noticed a substantial improvement among some of the contestants. We were on to the heavy hitters now.

Throughout the competition, I had only a loose sense of a rubric in my mind – I was keeping an eye out for a variety of aspects, but ultimately when it came to giving that final rating out of 10, I was relying on intuition and a gut feeling to bring it all together. Like all judgment, it was a balance between measuring them up to objective standards and a subjective feeling or intuition. My sense was that my fellow judges were primarily, if not solely, judging based on the latter, but I strove to incorporate both elements into my final score.

Of course, different contexts call for different ratios between the two judging paradigms of objectivity vs. subjectivity, or logic vs. feeling.

Allow me to illustrate.

One day while walking on a San Diego beach with a friend who had come to visit me for a couple weeks, we got to talking about our favorite bars and restaurants on beaches. However, we were quick to point out that when establishments advertise that they’re located “on the beach,” that can mean drastically different things.

Some bars that say they’re on the beach are quite literally on the beach, with sand blowing into the building. Other times, and alas more commonplace, such “on the beach bars” are nowhere near the beach, and you would be lucky to catch a glimpse of the ocean from the top floor.

And thus, the Beach Integration Tier System was born. As we strolled down that San Diego beach to a setting sun, we put in place a series of objective rules to determine how “on the beach” an establishment truly is – aka its beach integration tier.

The system follows a standard tier ranking methodology where the top ranking tier “S” includes those bars and restaurants that are closest to and most integrated into a beach. Following S tier, there were A, B, C, D, and finally F tier where describing the establishment as “on the beach” becomes more and more of a stretch, until finally with “F” it’s an outright lie.

Now you may be asking, why bother creating such a system? Why judge establishments on their level of beach integration anyways? Precision of language and thought – instead of using a binary term such as “on the beach” to describe a bar, we can be more precise and increase our resolution of description which consequently increases the amount of information we can convey. Also, it made for interesting conversation at the time, and, like I said earlier, isn't nearly all conversation some form of indugling in or sharing judgements anyways?

Viewing bars and restaurants near the beach through the lens of the Beach Integration Tier System is akin to having poor eyesight and wearing glasses for the first time – it provides clarity to what you’re seeing, understanding, and a common language. In short, we have distilled some semblance of order from chaos. That is the purpose of judgment.

The rubric behind the Beach Integration Tier System is purely objective. There is no space for subjectivity or bias. For instance, a bar can never rank higher than a D tier if there is a street for motor vehicles that lies somewhere between it and the sands of the beach. This is a non-negotiable.

However, this rigidity in the ruleset leads to a few “glitches” in the system. The presence of any building or natural barrier, such as trees or foliage, that lies between the bar and the beach would put the bar in question squarely into the C tier. No exceptions. As we were discussing this particular rule, we happened to be walking by a seafood restaurant that appeared to be quite directly on the beach.

“Aha!” I exclaimed, “there’s a coveted A tier restaurant!” (it’s of note that true A and S tier establishments that are literally on the sands of a beach are surprisingly rare, especially in the US. Less so in other countries perhaps.)

“Not so fast,” my friend retorted. “See there? Those are bushes growing at the base of the restaurant, technically creating a natural foliage barrier between it and the beach. I’m afraid it’s only a C tier establishment.”

As painful as it was to admit it, given our ruleset, he was correct. The Beach Tier Integration System is ruthless and unforgiving.

Of course, given enough time to account for every edge case and odd situation, it likely is possible to formulate a relatively “glitch-free” tier system for ranking beach integration. But how can we say when the hypothetical system is “perfect”? When the objective ranking system most closely resembles some fuzzy intuition we all collectively share, can we say that it’s ideal.

But the whole point of creating an objective system was to remove the subjective element. It is true that given the rules, it is purely objective – there is either a street in front of the bar or not. There’s no wiggle room there. But the choosing of the objective standards is a subjective process, and there’s no getting around that.

In other words, for any given judgment system, the chosen standards or rubric are a reflection of the values subjectively believed to best represent whatever it is being judged. The actual measurement of each standard or criterion in the rubric may even be objective (as is the case with the Beach Integration Tier System), but how well the rubric itself reflects that which is being judged may be up for debate. This is one reason we were so adamant to precisely define the Beach Integration Tier System as a system that solely ranks how integrated an establishment is with a beach – it’s not giving any commentary on if it’s “good” or “bad”; it’s an objective measurement of beach access. No more, no less.

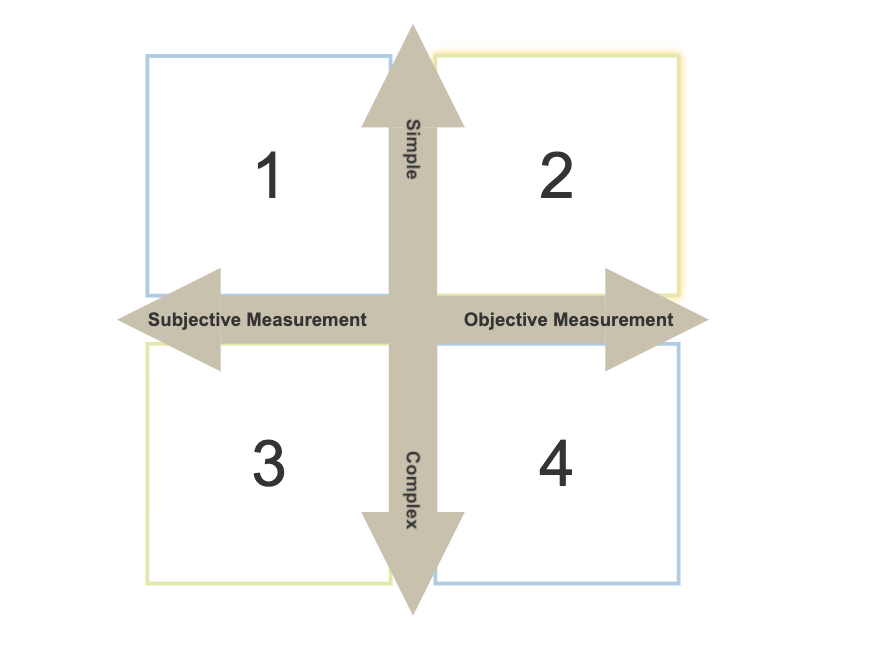

With the understanding that the alignment of a system’s rubric and the target of judgment may always have some degree of subjectivity, we can imagine a 2 by 2 matrix for describing different judgment systems. One axis represents the level of complexity in the rubric, or how many criteria it takes into account. In reality it’s a sliding scale, but for our purposes, let’s consider it as either simple or complex. The second axis represents whether the rubric’s criteria can be measured objectively or if it’s subjective. Again, technically a spectrum, but we can consider rubrics to be only one of the two here.

In the first quadrant, simple-subjective, we have the vast majority of everyday judgments. Most people incorporate little-to-no rubric when making quick judgments. A restaurant was either good or bad, maybe they take the atmosphere into consideration, but no more than a handful of variables. My fellow Slam Poetry judges likely resided in this quadrant.

The second quadrant, simple-objective, is where I place the Beach Integration Tier System. As powerful a system it might be, its ruleset is relatively simple (as evidenced by its “glitches”). The more limited the ruleset, or rubric, the clearer the target of judgment. Because it’s simple, it’s easy to investigate each dimension being measured and to conclude whether or not the rubric is well chosen for its purpose.

The third quadrant, complex-subjective, is home to more structured rating systems. To give an example, my friends and I started a movie club some time ago (formerly a book club, but we got lazy) where a large part of our conversations revolved around rating movies. In the beginning we each gave a single rating 0 to 5 to the nearest quarter point (simple-subjective). Over time, however, we made our rating system increasingly more complex – we would give a 0 to 5 rating for cinematography, acting, soundtrack, plot, and characters. We would average these components together to get a cohesive rating. It’s important to note that for each of the criteria, there’s a large degree of subjectivity in the scoring process.

Finally, we have the fourth quadrant, complex-objective. This is the realm of artificial intelligence and other complex classification systems. A computer program that implements a neural network to recognize rabbits, for example, will be trained on a large dataset of rabbit and non-rabbit images. After exposure to enough of these training inputs, the neural network will have devised a complex rubric of sorts (not easily understandable by a human) that when given a never-before-seen image, will be able to detect if a rabbit is present or not with a high degree of confidence.

It’s important to stress that these artificially created “rubrics” can get so complex that we cease to understand how they’re making decisions, which can lead to some unexpected phenomena. This is an exaggeration of the earlier point that a rubric is a reflection of the values subjectively believed to best represent the target of judgment – at this level, sometimes the features or “values” a computer picks up on stray far from being relevant to its goal or the target of judgment. When this happens, it results in “glitches” like the one we saw in the Beach Integration Tier System.

An interesting observation here is that a system in quadrant three (complex-subjective), when made complex enough, will slowly transition and get closer to quadrant four. In other words, as a subjectively measured rubric adds finer and finer dimensions of judgment, the less subjective and more objective it grows to be. Take James Cameron’s recent film Avatar: The Way of Water, for example. With a simple one dimensional rubric, there’s bound to be some level of disagreement over what to rate the movie – some will say it’s cliché and predictable and rate it poorly, while others will appreciate the graphics and rate it highly.

If we focus in on one criterion from a more complex rubric, such as cinematography, there will likely be less variance of opinion since the scope of what’s being rated is narrower, but of course there’s still a level of subjectivity. However, if we zoom in to an even finer level of detail, and analyze the quantity of levels of depth of composition of each scene, and assigning a numerical grade based off the results, then we’re entering into a more objective rating (side note: Avatar: The Way of Water had an astounding level of depth in many of its scenes compared to the first Avatar due to massive improvements in computer graphics technology).

Imagine the hypothetical scenario where an AI creates a rubric for reviewing movies that is fantastically complex, taking every objective detail into account. Would its final score be the Truth with a capital T? Yes and no.

It would be consistent to its own rubric, but, again, the rubric itself is a reflection of the values believed (in this case, by the AI) to best represent the target of judgment (here, it would be how good the movie was). While rubric complexity is directly proportional to objectivity, both are inversely proportional to certainty – where certainty here represents how confidently we can align the final judgment using a given rubric with our understanding of what is actually being judged.

Rubric Complexity ∝ Objectivity ∝ 1 / Certainty

Just as we’re unable to fully grok how a neural network is able to detect a rabbit, given a complex enough rubric such that it’s approaching total objectivity, we cannot be sure it’s judging the “goodness” of a movie as we understand that to mean. The issue here, however, lies not only on the side of understanding an infinitely complex rubric, it also lies on the side of understanding what our own seemingly simple concept of “goodness” of a movie means. What makes art good – what makes art art? More on this later, but for now, consider: is it possible to dissect the human concept of “goodness” or “art” into a series of objective measurable dimensions? Perhaps.

If we accept that the subjective or the intuitive can be hypothetically dismantled into an extraordinarily complex set of objective measurements – but practically never verifiably so because certainty will trend to zero as objectivity and complexity increase – then introducing subjective measures or intuitive feelings into a rubric can be considered heuristic approximations of infinitely complex, and unknowable, objective details.

In short, what I’m saying is that a well tuned intuition is equivalent to massively powerful computation that due to the nature of reality, we will never be able to fully decipher.

This is all to say, subjective feeling and intuition do indeed have an important role to play in judging (yes, I know, I have simply proven the obvious). If you made it through the past several dense blocks of text, I congratulate you and thank you for sticking it out. Anyways, back to the story.

The second to last round was beginning. The heavy hitters. There was no holding back now, these poets were fully expressing themselves, letting everything out, and being vulnerable with the audience in a way I had never seen before.

As I alluded to earlier, a common theme I picked up on was this venting dynamic where a poet would divulge an injustice or pain they had in life, and the audience would react with validating noises, ranging from subtle snaps to full blown “Yeah gurl!”’s and “F*ck ‘em!”s. I cannot deny that such exchanges would fill the room with a palpable emotional energy. Tensions would build, only to be explosively released in a final expression of pain. It was a symphony of suffering. To me, it was nearly paradoxical in its beauty – like a beautifully constructed mansion, but built from rotten wood.

Are we to judge art by how it moves us? Or by where it moves us to?

In a society that has become increasingly swayed by concepts like relativism and nihilism, it becomes easy to disregard the quality of content and overly fixate on the intensity of content.

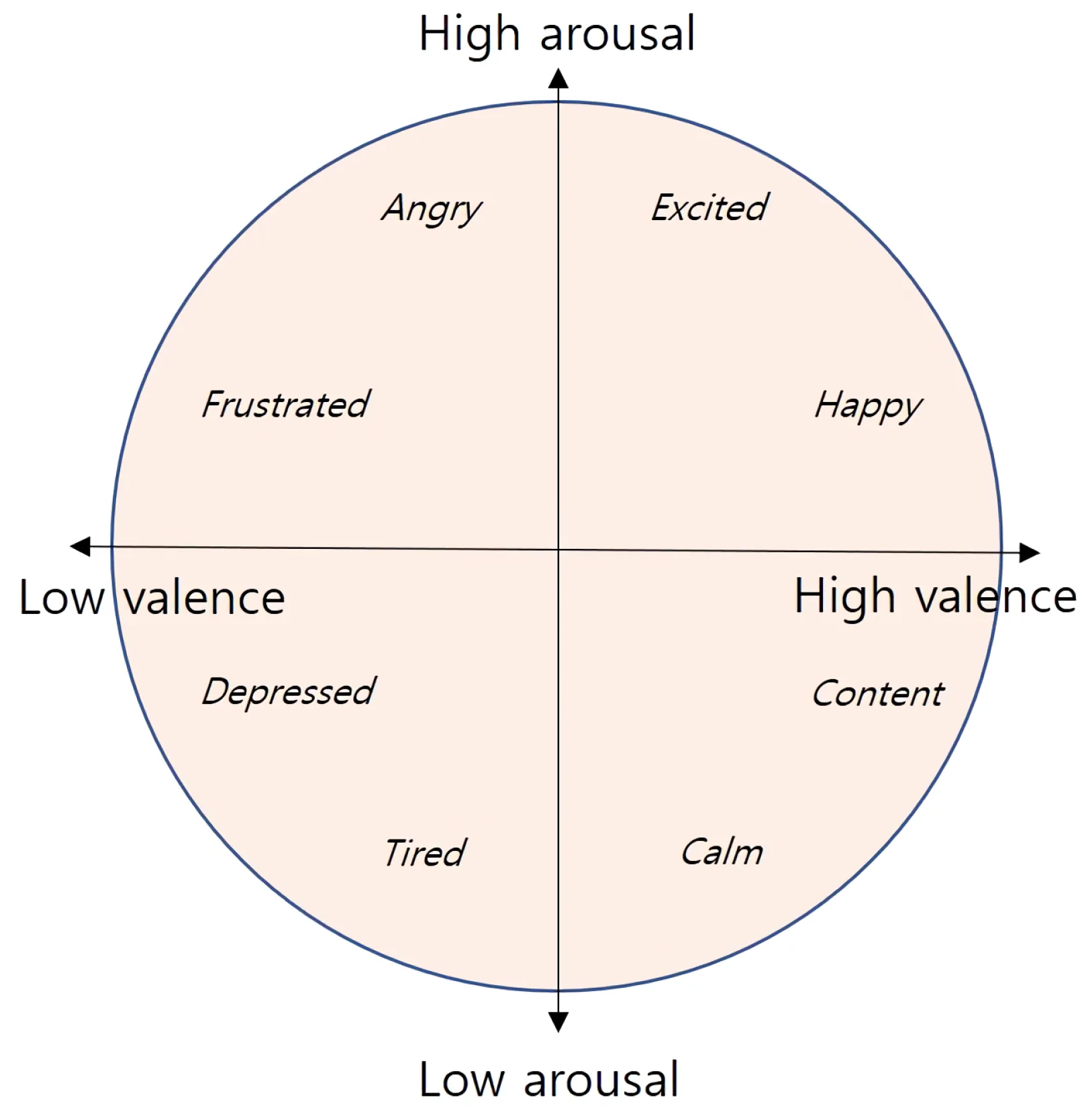

A common map for modeling the range of human emotion is called the Circumplex model of emotion. It involves putting valence, or how pleasurable an emotion is, on the x-axis, and arousal, or how intensely you experience an emotion, on the y-axis. A high arousal, high valence emotion would be joy or enthusiasm; low arousal, high valence emotion would be peacefulness; a high arousal, low valence emotion would be anger; and a lower arousal, low valence emotion would be depression. And there’s everything in between.

Traditionally, art has tended to evoke feelings high in valence. A serene portrait of a landscape, for instance, conjures a sense of peace. An orchestra reaching the crescendo of a Mozart overture rouses feelings of joy. But of course, there are countless examples of art playing in the other two quadrants of emotions – a punk rock band riling up feelings of anger, or a Greek play ending in tragedy.

This begs the question, why do we subject ourselves to art that makes us experience displeasure? Does this not defy the pain-pleasure principle, our natural tendency to move towards pleasure and away from pain?

I took a music and cognitive science class in college where we explored how and why we experience music the way we do on a biological level. One question our professor posed was why do we listen to sad music? The answer, at least biologically, is quite simple – melancholic music boosts hormones such as prolactin which, in turn, can enhance feelings of calmness and ward off grief.

But if all negative emotions release a cocktail of feel-good hormones every time we experience them, we should have anger and grief junkies, not heroin addicts on our streets. However, on further reflection, we realize that our world is indeed brimming with anger and grief junkies.

In the 1960s, psychiatrist Robert Heath ran an experiment where he placed electrodes in participants’ brains and allowed them to stimulate nearly any feeling or emotion they desired. With the click of a button, participants could choose to feel joy, sadness, anger, sexual desire, and more. Interestingly, with the whole array of human emotion at a fingertip’s notice, participants chose to trigger anger more than anything else.

Biologically, the explanation is that anger triggers a strong release of dopamine, a feel-good/reward neurotransmitter. Makes sense, right? But it makes one wonder – why should learning a simple biological truth about our own bodies be so surprising to our conscious minds? Why don’t we know this from a lifetime’s experience of dealing with anger and feeling releases of dopamine? Shouldn’t this have been obvious to us?

Oftentimes it’s easier to see it in other people. We all have that family member or friend who is seemingly addicted to an emotion. He or she may take every opportunity they can get to rise to anger or fall into sadness. But if you point it out, they deny it’s their choice, or their preference. Clearly though, some part of them, probably not a conscious part, is milking that feeling for the neurotransmitters it releases, out of habit, or for whatever other reason.

A person is a people – that is, our psyches are comprised of a multitude of sub-psyches, each with their own agendas, needs, and preferences. This rabbit hole is a topic for another time, but essentially we say a person is “possessed by anger” because another sub-psyche in their mind is taking the reins and enjoying its time being active. So when asked if we enjoy being angry, the part of us answering is ignorant to the part of us that does indeed enjoy it.

Depending on the composition of a person’s sub-psyches, they may seek out art and experiences that evoke all sorts of emotions and be unable to articulate why they feel so drawn.

But despite our deep dive into emotion, it doesn’t help us much to answer the question of how to judge art. Are there right and wrong emotions (or combinations of emotions) to be on the lookout for when judging a piece of art?

As I sat in quiet contemplation listening to a young woman in a pink polka-dot skirt unleash a barrage of terrible injustices that had befallen her (all in rhythmic meter, mind you), I couldn’t help but to feel a collage of feelings – empathy, sympathy, pity, and anger. Looking around, the audience was on a similar wavelength, exchanging sympathetic sounds and validating hoots when appropriate.

And then her three minutes were up and it was over. The audience erupted into thunderous applause, but I felt a little empty.

How was I going to judge this one?

Evolutionarily speaking, emotions serve their purposes. Fear protects us from danger. Anger compels us to take action. Actions that result in happiness tend to be adaptive and beget more positively adaptive actions.

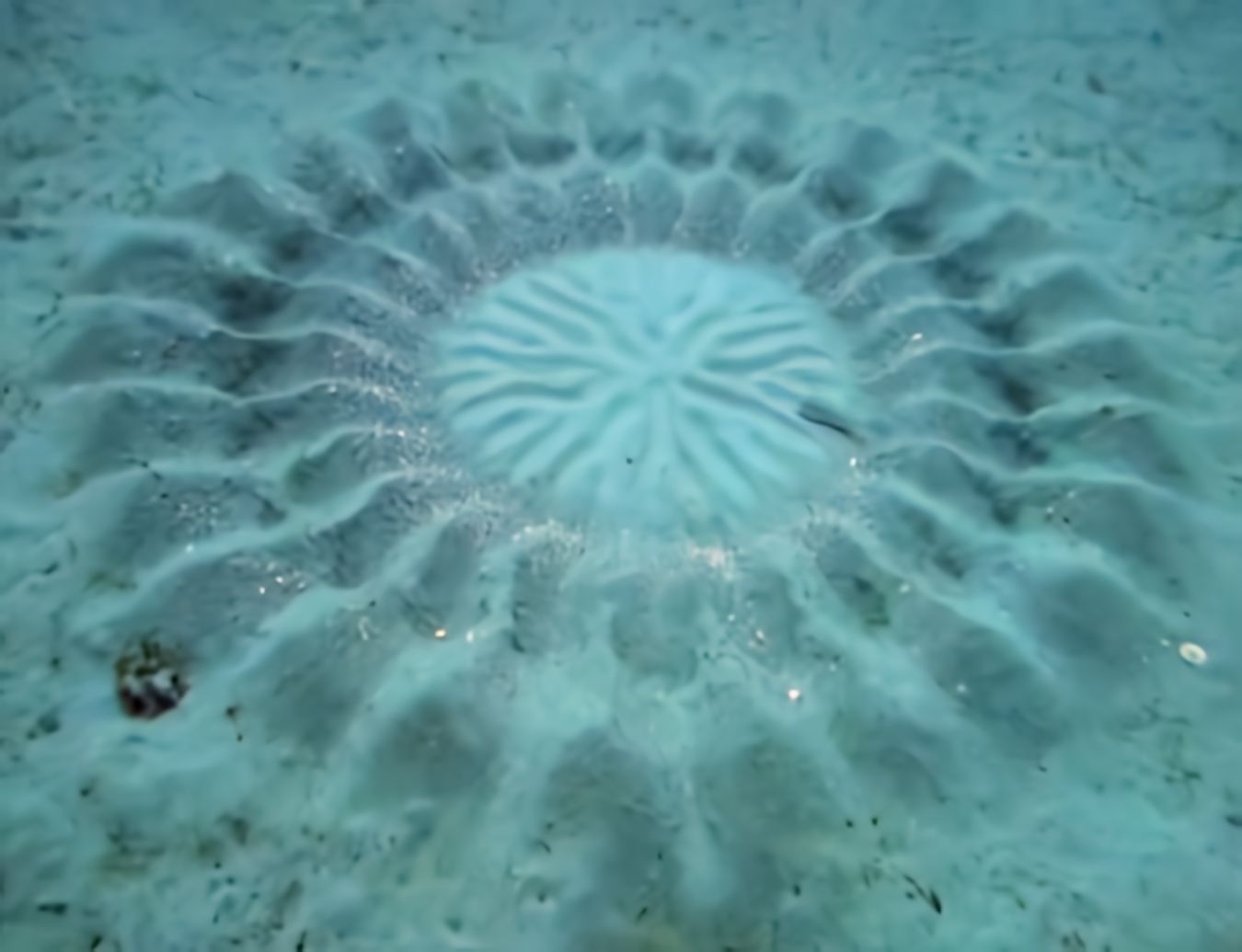

But what is the evolutionary purpose of art? Some argue we developed art because it brought communities together and communicated survival strategies. Others say it was for the purpose of attracting the opposite sex. In fact, there's a species of puffer fish that constructs beautiful mandalas drawn in sand on the ocean floor in order to attract a mate.

The fact that the sand art of a puffer fish is considered aesthetic by us humans on the other side of the Animal Kingdom, paints art as a universal, inter-species language. Patterns such as the golden ratio are as ubiquitous among manmade inventions as they are natural marvels.

The defining quality of art is that it is order in the midst of chaos. It is entropy reducing. And for order to appear, there must be some amount of patterning or harmony present.

When we view art through a psychological, or even a spiritual, lens, we see that art allows us to experience a part of ourselves, a sub-psyche or collection of sub-psyches. The order expressed in art has the power to change the way we relate to those affected sub-psyches; it resonates with meaning that can alter our perspective. It changes us.

Art drives evolution. On a macro and physical level, we see that when the conditions necessary for life arise – abundant water, carbon, a stable atmosphere – order has arisen from chaos and life can thrive. On an inner and personal level, art challenges us to wear new perspectives that can help us find meaning and order in the chaos that is life.

Evolution drives art. On a macro and physical level, we human beings (and puffer fish) evolved over millions of years through the pressures of natural selection only to now express ourselves through art, creating order where there once was chaos. On an inner and personal level, our growth in character manifests as taking creative action in the world.

While the individual components of a piece of art may evoke emotions all over the Circumplex model of emotion, the whole when viewed from afar must provide some harmonizing order arising from chaos, which we experience intellectually as meaning and emotionally as feeling second order high valence. Meaning emotions in the moment may be negative, but we relate to them overall positively. Order from chaos is beauty is meaning is bliss. This is art.

And so I needed to go with my heart – I couldn’t in good conscience give the pink polka-dot skirted lady a rating higher than seven, despite her rhythmic flow and expressiveness. I couldn’t articulate it at the time, but the overwhelming negative outlook on life she conveyed, while entirely understandable given her unfortunate life story, darkened my soul – I yearned to hear words that would expand my spirits, resonating the sub-psyches in my mind in novel ways to come together and find new meaning in the world. Maybe a lot to ask, but nobody said art is easy.

To my surprise, I wasn’t the only one that gave her a lower than perfect rating. Most stuck with giving an extremely high rating (at this point in the night, grade inflation was a thing, and 9s and above were being handed out like free candy), but one or two other judges gave similar ratings to mine. Perhaps even here, where sub-psyches of pain, sympathy, and anger ran rampant, there was a universal yearning for meaning present.

It was the final round. Only the top three would move on to regionals. The final competitor to close out the night walked up to the stage. I recognized him from an earlier round. I remembered I was quite impressed by his earlier performance – he had a strong and clear voice that filled the room and unlike many of the other competitors, he knew his poem fully by heart (something I took into account with my ratings), which allowed him to more freely gesticulate and express with his arms. He even looked as you’d expect a poet in the 21st century to look like – maybe mid-30s, slender tall build, dark brown hair pulled back in a ponytail, and two full tattoo sleeves. But most importantly, I’d found real meaning out of his first performance – he expressed the full range of human emotion, but it wasn’t merely a string of sufferings. It harmonized together as something greater than the sum of its parts, leaving me with new outlooks and thoughts. This man was the total package. And I was excited to see what he had prepared for the final round.

As he began, he immediately met and then exceeded my expectations. There was a musicality to his lines beyond mere rhymes – each word set up the next word in meaning and sound, each line set up the next line leaving me spellbound.

Other than the impressive wordplay, I think he captivated us the most by bringing us through a wide diversity of human experience. His words transported us to every corner of the Circumplex model of emotion, but not in a haphazard manner – they told the story of his life, which was a reflection of the story of Life, a story we can all relate to: ups and downs, descending into grief to find hope, discovering our courage to face fear.

He was about half way through, relaying a painful experience in his life where he had hit rock bottom, when he took a pregnant pause. A perfect moment to build the suspense, to grow the tension around the climactic point of desolation in his life and immediately before what we could only assume would be his triumphant climb back to wholeness.

The pregnant pause grew more and more overdue, until it became clear it was no longer a tension building device, but a lapse in memory. My heart sank as I saw the pain of his past experiences transform into pain of the present moment with his face contorting and his eyes darting back and forth in a desperate attempt to retrieve the next line from memory. All the while, the crowd remained silent in nervous anticipation.

As his silence grew longer to the point where it seemed he would be forced to end prematurely, a few people in the audience broke the awkward tension with words of encouragement.

“You can do it!”

“You got this!”

A few turned to several, and several turned to many, until it was a tidal wave of supportive cheers from the audience washing the stage with their vocal positivity.

And in an instant, he was back. The dam broke, and a flood of expressive words began to flow once more.

He pulled himself out of rock bottom, not only in the poem’s story as he was at the precise moment of getting his life back together after an immense tragedy, but in the performance as well with the remembrance of the next line. Such an uncanny symmetry between poem and performance, past and present, that I couldn’t help but to wonder to myself if it was more than mere coincidence.

He closed out the poem with just a handful of minor hiccups in memory, but the audience was with him every step of the way, amplifying their supportive words of encouragement whenever necessary. When he finished, the audience erupted into thunderous applause and cheering. The loudest of the night by far. He was a fan favorite, and understandably so.

It was time to judge one last time.

It should have been an easy rating to give. It should have taken me no longer than several seconds to judge his performance as absolutely excellent. And I wanted nothing more than to give him as close to a 10 as I reasonably could for giving such a moving performance.

But the lapse in memory he had halfway through threw a wrench into it all. If it weren’t for that one innocent mistake, he would have been the easiest poet to judge all night. But things weren’t so simple now.

I know what it’s like to stand before an audience that sits in quiet anticipation having high expectations of you, only for you to let them down.

My sophomore year in high school, we had a grade-wide poetry competition. It was like the freshman declamation all over again, but for sophomores. We each memorized a poem of our choosing to perform before our class, and, again, like the previous year’s declamation, we were judged by a strict rubric.

Having won the freshman declamation, I entered the poetry competition with an air of confidence, even hubris. I started memorizing my poem only a couple days before the competition began. On the day of the competition, I still hadn’t fully memorized my poem, but my English teacher gave me the privilege of being the final performance the following day.

The day of my performance came, and my English teacher along with my entire class was excited to see how I would top my last year’s performance. I began reciting the poem, still confident in my abilities. The first stanza rolled out beautifully – I was hitting my stride.

And then I hit the wall. I was barely halfway through the second stanza and my memory completely failed me. I stood before my class frozen and silent. Worse, they were equally silent, sitting and staring back at me in quiet anticipation.

We expect times like these to be anxiety inducing and nerve racking, but I felt nothing. My heart rate slowed as I realized that I failed them. I failed my teacher, I failed myself.

Eventually, I managed to sputter out a couple malformed lines. But that was all I had, and after I soaked in my fill of embarrassment, I quietly walked back to my desk and sank into my seat.

On the one hand, my respect for the ponytailed poet grew because I knew the willpower it took to recover from what feels like a monumental failure. He succeeded where I had failed, and I admired him for finishing strong.

On the other hand, as a judge, it was my responsibility to give a fair and objective rating no matter how difficult that might be or what biases I might have. This was the job I volunteered for, and I took it seriously.

The entire night, I was trying my best to remain consistent to an internal rubric for judging the poets. It took a number of things into account, one of which being memorization of the poem. I had been giving a boost in score to poets who didn’t rely on reading their poems off their phones, and subsequently, a demerit for any cases of obvious forgetfulness (there had not been many of these until now). If I turned a blind eye to his forgetfulness now, would that cheating of the rubric not compromise ratings for the entire night giving him an unfair advantage over the others? How much could I bend the rules before the rules lost all meaning and any objectivity was lost?

I thought back to the Beach Integration Tier System and its ruthless and unforgiving nature. A rating system built on pure objectivity and logic that allowed no room for debate. If there was a “glitch” in the system, in order to fix it, the entire ruleset would need to be updated, and all prior ratings would need to be redone to account for a change in the rubric. A very different situation compared to this contest as clearly I couldn’t revise my ratings for the earlier competitors if I changed my weighting for memorization. So was I to remain as consistent and rigid in my scoring as the Beach Integration Tier System? Was I to be ruthless and unforgiving?

Pondering my final rating, my fellow judges were already beginning to hold up their scorecards for the MC to announce.

“9.7!” the MC called out. Roaring applause.

“9.9!” The energy in the room swelled.

I was under no oath to so strictly adhere to an arbitrary rubric I had set up for myself. Judging is a balance between feeling and logic, between the subjectively felt and the objectively measured. The intangible factor is paramount to take into account, and I understood that under the hood, that this X factor is a heuristic – it’s an intuitive approximation of an infinitely complex, but logical and objective, set of rules and conditions.

However, just as we struggle to understand how an extraordinarily complex system such as an AI detects rabbits, or what an equally complex rubric is really ultimately judging, it’s difficult for us to pinpoint exactly what our intuition or subjective sense is looking for to deem something as good or bad, and everything in between.

There is a universal nature to art that transcends cultural, and even inter-species differences. It is this formation of order emerging from chaos that strikes a chord within us that we experience as beauty and as many different feelings within the spectrum of human emotion, but ultimately as a degree of bliss, even if nearly imperceptible sometimes.

Was it just coincidence that his flow of memory halted at the moment he recounted his deepest despair? Was it happenstance that the words that finally came to him, when saved by the caring crowd, were words of picking himself back up in the face of failure and refusing to give up? Was the temporal symmetry between past grief and present anxiety both followed by courage and persistence a simple coincidence? Perhaps it all was coincidental, but even in what seemed to be a random mistake, despite its size, there was, from a certain perspective, a striking sense of order. An order that quite literally was born from chaos. And it was beautiful.

“9.8!” Announced the MC as the audience only grew louder and louder.

“A perfect 10!” The energy in the room hit an all time high.

As these thoughts swirled in my mind, I was out of time. It was time to give my rating. And I finally made my decision.

“And our final score is… oh. A 7.7.” The room died to silence. Part of me died too. And then the energy returned to its former all time high, but with a negative valence of yelling, booing, and angry glares directed my way that pierced me like javelins.

But I’d made my decision, and I stood by it. I couldn’t deny the ponytailed poet gave a rousing performance – I found it beautiful, it moved me. Ultimately, however, it was my duty to be ruthlessly honest and fair – to judge truthfully no matter the cost.

In the end, the ponytailed poet still received a high enough score to be placed in the top three and move on to regions. I was happy to hear that, I thought he deserved it. In my book, he was no undeserving jabroni en route to stardom, but a skilled wordsmith with a budding career.

As my friend and I and the rest of our group left the building to walk to a nearby brewery to decompress, I was surprised to hear they all were happy with my judging, even my final decision. No angry jeers from them, but only respect.

Every day, we judge. Every conversion we participate in, we judge and share judgments. Every thought we have is some form of judgment, on others, on ourselves, on the world. There is no escaping judgment. Those who try to lose the ability to judge lucidly and precisely and end up judging crudely and ignorantly.

The way we judge the world is the way we view the world. If we don’t know how we judge, from the micro to the macro, we fail to understand our own internal perspectives in life. Through a conscious exploration of how we arrive at our judgments, we learn how we think, what our true beliefs are deep down, and it allows us the peace to not be controlled by our judgments all the time. It gives us the space to spend less time in judgment, and more time appreciating the distillation of order from chaos that is constantly occurring around us.

So judge, judge as hard as you can! It’s your only freedom from a life spent in judgment.